The Allure of Marxism … And Why It’s a Mistake

November 26, 2019

Originally published on Economics from the Top Down

Blair Fix

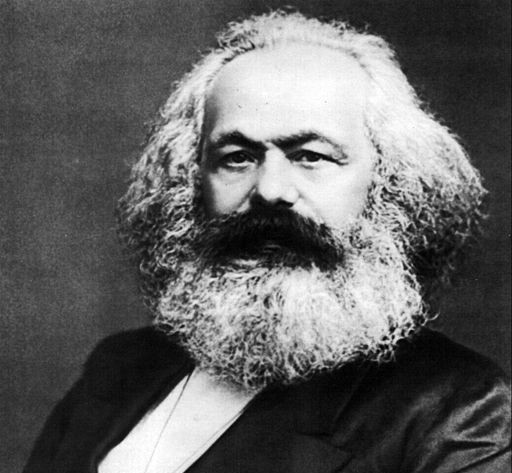

Karl Marx is probably the most important social scientist in history. But while his influence is beyond compare, Marx’s legacy is, in many ways, disastrous.

Few thinkers have inspired so many people to commit crimes against humanity. Think of Stalinist gulags. Think of the Ukrainian famine of the 1930s, which may have killed as many people as the Holocaust. Think of the Great Chinese Famine of the late 1950s, which killed even more people than the Holocaust. All of these crimes were driven by Marxist policy.

An obvious problem?

OK, many of you are probably wondering where I’m going with this discussion. You’re thinking to yourself: yes, it’s obvious that Marxist ideas led some people to do nasty things. So why do we need to discuss it?

The problem is that it’s not obvious to everyone. Many Marxists don’t connect the crimes of Stalin and Mao directly to Marx’s ideas. Instead, they dismiss these crimes as aberrations. These crimes, they say, were unfortunate consequences of bad people or bad circumstances. Marxism itself was not the problem.

I’ve experienced this thinking first hand. I once took a class taught by a professor who was a militant Marxist. One day, a student asked the professor what had gone wrong with the Russian revolution. The professor’s response surprised me. The revolution, he said, was going well until Lenin died. Then Stalin took over. It was Stalin, the professor insisted, who hijacked the revolution. Had Lenin remained in power (and found a better successor), things would have gone differently.

Now, like me, you’re probably skeptical of the professor’s response. But ask yourself — what’s wrong with his explanation? What’s wrong with pinning the problems of Soviet Russia on Stalin?

Here’s a gaping flaw. When it comes to communist revolution, leaders like Stalin are not the exception. They are the rule. Think Mao. Think Pol Pot. Think Kim Jong-Il. For reasons that Marxists don’t like to think about, communist revolutions frequently end up with despots running the show. So if despots seem to take over Marxist revolutions, it’s hard to argue that Stalin was an aberration.

If we don’t buy the ‘aberration’ argument, then we need to ask a question. Why do communist revolutions usually lead to despotism? Is it just bad luck? Unlikely. I think there’s something deeper going on. I think the problem has to do with Marxist theory itself.

Why do communist revolutions lead to despotism?

Communist revolutions end badly, I believe, because they are based on faulty ideas. The problem is that Marxists misunderstand the source of capitalism’s social ills. It all goes back to Marx himself.

Marx pinned the ills of capitalism on private property. I think this was a mistake. The real cause of most social ills, I believe, is not private property. It’s hierarchy. Why? Because hierarchy concentrates power. And concentrated power is the despot’s best friend. Concentrated power, I believe, leads to social ills like totalitarianism, inequality, mass violence, and oppression. True, private property is intimately linked with hierarchy and power. But, as communist states demonstrated, we can have hierarchy without private property. This is Marx’s fatal error.

So here’s what goes wrong with communist revolutions. Distracted by private property, Marxist revolutionaries make the problem of hierarchy worse than it was under capitalism. They abolish private property, thinking this will solve the problems of capitalism. But to achieve their goals, Marxists create a vanguard party that eventually becomes a single-party state.

So in the name of creating a more just and equitable society, these revolutionaries concentrate power. They replace capitalist hierarchies with an even larger communist hierarchy. Yes, private property is gone. But the problems of hierarchy are even worse than before. It’s an ironic twist. Marxist revolutionaries aim for a socialist utopia. But what they get is a totalitarian nightmare. And it’s all because they focus on private property and neglect the problem of hierarchy.

Marx’s theory of capitalism

To understand why Marxist revolutionaries fixate on private property, we need to understand Marxist theory.

Capitalists, Marx observed, own the tools and machines that workers need to do their jobs. By owning the ‘means of production’, capitalists are able to exploit workers and extract a ‘surplus’. Capitalists, says Marx, are parasites. They live off the backs of workers.

I’ve tried to visualize Marx’s theory in Figure 1. Here we have a group of workers (‘labor’) who collectively produce something of value. To do their jobs, the workers must use construction machines. We call this machinery ‘capital’.

Figure 1: Visualizing Marx’s theory of capitalism.

Figure 1: Visualizing Marx’s theory of capitalism.

Here’s the catch. The capitalist owns the capital. So to do their jobs, the laborers must work for the capitalist. Now comes the crucial part. According to Marx, it is workers who create all the value. But since the workers are employed by the capitalist, they don’t own the value they create. The capitalist owns it. And unsurprisingly, the capitalist takes a cut.

So here’s the crux of Marxism. Marxists think that by owning capital, capitalists can take a cut of the value produced by workers. Marxists call this cut ‘surplus value’. It’s value that is produced by workers and stolen by capitalists. That’s Marx’s theory of capitalism in a nutshell. It’s simple, seductive, and incendiary.

Private property as an ideology that justifies hierarchy

Here’s the problem with Marxist theory. I don’t think that private property is the true problem. Private property is just an ideology that justifies hierarchy. And it’s hierarchy, I believe, that is the real social evil. Hierarchy concentrates power, leading to many forms of debauchery.

With hierarchy in mind, let’s take another look at the role of private property in capitalism. Marx focuses on the ownership of things — the tools and machines that workers’ use to do their jobs. But I think this is a distraction. What is really important is the ownership of institutions.

When you own an institution, in effect, you own a hierarchy. But it’s not the ownership itself that is important. It’s the fact that ownership is what legitimizes your power. As the owner of hierarchy, you are the legitimate ruler.

Let’s illustrate this principle using a modern example. Think about what it means to purchase all the shares in a company. What are you buying? I argue that you are buying hierarchical power. As owner of the company, you gain the right to command the corporate hierarchy. Your subordinates obey your commands because, as owner, they believe you are the rightful ruler.

I’ve visualized this thinking in Figure 2. Here we have a capitalist who commands a corporate hierarchy. As ruler, the capitalist is able to split the firm’s income stream. The capitalist keeps some of the income (as profit), and pays the rest to workers. We think of capital not as ‘thing’, but as the symbolic power of the owner.

Figure 2: Private property as an ideology that legitimizes hierarchy. Rather than a ‘thing’, we conceive of private property as an ideology. As owner, a capitalist is the legitimate ruler of a corporate hierarchy. The capitalist uses his/her power to divide the firm’s income stream. My thinking here combines my ideas about hierarchy with Jonathan Nitzan and Shimshon Bichler’s theory of capital as power.

Figure 2: Private property as an ideology that legitimizes hierarchy. Rather than a ‘thing’, we conceive of private property as an ideology. As owner, a capitalist is the legitimate ruler of a corporate hierarchy. The capitalist uses his/her power to divide the firm’s income stream. My thinking here combines my ideas about hierarchy with Jonathan Nitzan and Shimshon Bichler’s theory of capital as power.

So here’s my main point. I think Marx looked at private property the wrong way. Private property is not the source of our social ills. Private property is just the ideology that justifies hierarchy. And it is hierarchy (and the concentration of power that goes with it) that is the true source of our problems.

The many ideologies of power

When we treat private property as an ideology of power, something interesting happens. We realize that banning private property won’t solve any problems. Why? Because there are many ideologies of power. [1] Banning private property just leads to a new ideology of power. And so the problem of hierarchy continues.

Here’s an interesting way to look at communist revolutions. In a matter of years, they reveal the same pattern that human history shows over centuries. What’s the pattern? That hierarchy is a consistent part of civilization. You can change the ideology that justifies hierarchy, but hierarchy itself doesn’t go away.

Take a long-term change — the transition from feudalism to capitalism. Over centuries, the ideology of power changed. In feudalism, power was justified by religion. (Think of the divine right of kings). But in capitalism, power became justified by private property. The ideology of power changed, but hierarchy itself didn’t go away. If anything, it grew.

Communist revolutions show the same trend, but over a matter of years (not centuries). In one fell swoop, communist revolutionaries abolish private property. In effect, they instantly kill the capitalist ideology of power. They also usually ban religion, and so kill the ideology of feudal power. But do communist revolutionaries abolish hierarchy? No! They remain slavishly devoted to it, probably even more so than under capitalism.

After killing the old ideologies of power, communist revolutionaries adopt a new one. They created a secular religion — a belief in salvation through socialist utopia. Then they used this ideology to concentrate power.

Marx would probably be horrified if he had lived to see his ideas put in action. At least for a time, communist revolutionaries made Marxist thinking a more potent ideology than private property or religion ever were. In the name of Marx, communist regimes plumbed the depths of totalitarianism. Millions died as a result.

Marx underestimated the scale of the problem

Marx argued that there is a simple solutions to the problems of capitalism. Abolish private property, he claimed, and a socialist utopia would follow. But when Marx’s ideas were put in action, they failed spectacularly. Marxist revolutionaries wanted a socialist utopia. Instead, they got a totalitarian hell.

I’ve tried to explain here what went wrong. Basically, Marx underestimated the scale of the problem. Our problem is not private property. Our problem is hierarchy, and the concentration of power that goes with it. Marxist revolutionaries showed that we can abolish private property. But no (lasting) revolution has ever abolished hierarchy. Revolutions just replace one ideology of power with another.

The point that I’m trying to drive home is that hierarchy seems to be a consistent part of civilization. It has been for thousands of years. So barring the collapse of civilization itself, it’s unlikely that hierarchy will vanish any time soon.

So it looks like we’re stuck with hierarchy, and all the social ills that go with it. But that doesn’t mean that we should give up the goal of seeking a more just and equitable society. It just means that communist revolution is not the answer.

Are there answers to the problems of hierarchy?

I believe the answer to our hierarchy problem is simple — make those in power more accountable to their subordinates. Yes, this is simple, but it’s devilishly hard to do. Bottom-up accountability runs counter to the top-down command that those in power love.

Still, over human history we’ve made modest gains in holding those in power to account. We have democracy, however limited it may be. The answer to our hierarchy problem is more democracy. I think it’s doubtful that we’ll get this through revolution. Instead, the march to hold power to account will be a long slow process, fraught with many failures and set backs.

Notes

[1] Jonathan Nitzan and Shimshon Bichler have an apt name for the relation between ideology and power. The call it a mode of power.